George Walter Vincent Smith George Walter Vincent Smith

George Walter Vincent Smith is widely considered one of the original pioneers of art collecting in the country. He is founder of the George Walter Vincent Smith

Museum, serving as its director after having given his entire collection to the Springfield (MA) Library Association. He had a scrupulous eye for quality and value. His taste was

varied and was meticulously driven by an object's beauty rather than being strictly an object of art that sat on a mantle or hung on a wall. A shrewd and gifted dealmaker, he began

his collection at the young age of 24 while working in the fabric importing industry. During that time he became enamored with the treasure hunters who scoured the world for rare

and interesting antiquities. Despite his remarkable business aptitude, which would have surely made him a very wealthy man, he opted to pursue and share his passion for beauty.

Asked once what advice he had for the youth, he answered, "Choose your companions with care, seeking those of principle and character rather than those of wealth. Be sincere, be

honest, observe the golden rule, and believe that there are other things more productive of happiness than the acquiring of great wealth."1

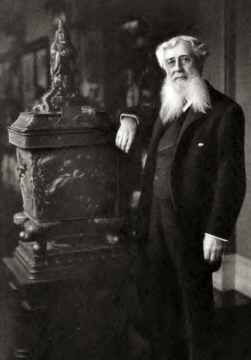

G.W.V.Smith in Japanese robe

George Walter Vincent Smith was born in New York City or Derby, CT, June 14, 1832 (reports vary). His father, George Wilson Smith, was a successful editor, printer and publisher. His father died when

he was just two and a half years old. His mother, Sarah Henrietta Wheeler Smith, of Bridgeport, Connecticut, left New York with her son to move home for a brief period

of time before eventually settling in the little village of Amenia, near the Connecticut line in Dutchess County New York.

Smith, born Methodist, would attend the Methodist

run Amenia Seminary for his primary education. His strong interest in geography, travel, and history were evident, even at an early age. Understanding that the seminary

education was somewhat limited, his mother provided him private tutors to round out his education. It is not clear why Smith, given his passion for it, did not pursue a profession in

art itself. Maybe he didn't have the skill or natural talent of hand to create his own work but whatever the case, at age 18 he would return to New York City in pursuit of a career.

In 1850, Smith went to work for fabric importer Babcock Gould & Company. Gifted with a sharp eye for quality and a sound business acumen, he would rise quickly in the firm.

After six years he rose to the position of confidential clerk and manager, after which he was then offered a partnership. He would decline the offer. During his time with Babcock Gould &

Company the job would serve as a preparatory school. He regularly came in contact with many men who "rummaged the world for curiosities as well as things of common utility."

2Their life had a seductive influence on Smith, whetting his own appetite for the hunt of treasures.

Chinese Cloisonné Chinese Cloisonné

The origin of the story of Smith's foray into art collecting is told by Samuel Atkins Eliot, which he recounted in a profile of Smith in his book, A Biographical History of Massachusetts.

"Into the shop, one morning, came a young man who was in the importing business, and in touch with goods from foreign lands. He saw the vase and was immediately attracted by it.

After an examination he bought it, and thus began a celebrated collection." 3 The vase was a particular style of Chinese pottery

called Cloisonné. Smith's collection of Cloisonné would one day become one of the most extensive collections in the world outside of Asia. Smith was just 24 or 25 years old at the time.

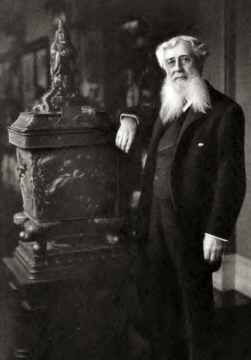

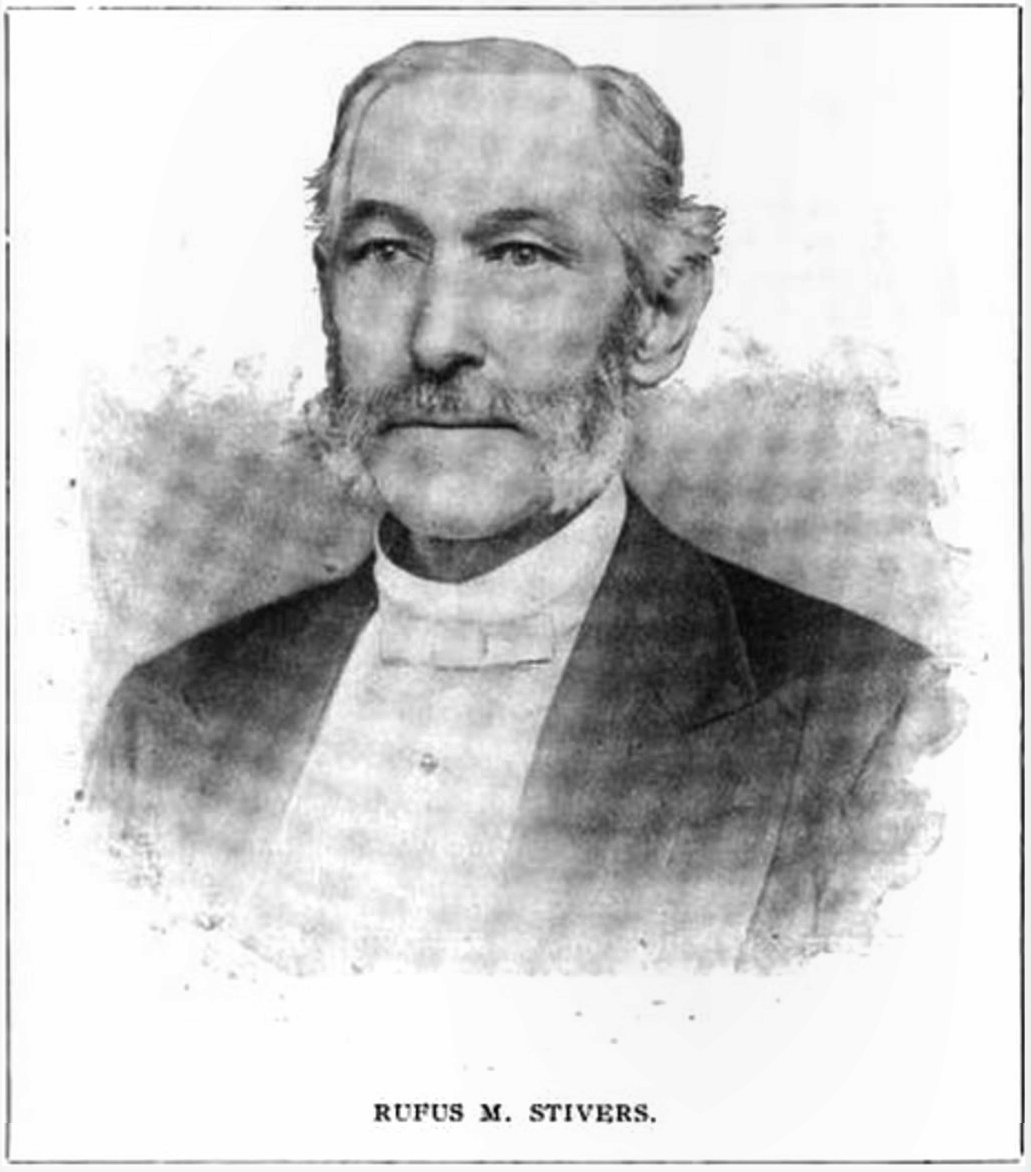

Carriage-Maker Rufus M. Stivers

His pursuit of collecting antiquities came at a fortuitous time. It was prior to the age of the "millionaire collectors," such as, the Carnegies, the Vanderbilts, the Havemeyers and Moores.

This would have naturally invoked competition and driven prices up. The professional and/or amateur collector was even a rarity. Collecting had not yet become fashionable. Still,

Smith would need an income and resources to foot what best could be described at this time as an avocation or hobby. So he decided to embark in business for himself. He chose

carriage-making, and with partner, Rufus M. Stivers formed Stivers & Smith Carriage Manufacturers in 1856 at just 24 years of age.

Rufus Stivers had been in the carriage-making business beginning in 1850 several years before the boom of 1857. His original partner, a blacksmith named Wilcott, retired after just

1 year together in which Stivers then partnered with another man named Conklin. Conklin would then retire in 1853 after just two years. Stivers would be alone for four years before

partnering with G.W.V. Smith. According to an account in the trade magazine "The Hub," Smith brought with him enough capital to open a repository on Broadway and later a factory on East

31st Street in New York City. Stiver's partnership with Smith was decribed as "special" and lasted long after Smith's withdrawing from the day-to-day operations in 1867. As of 1897, the

company's name was still listed as Stivers & Smith.4

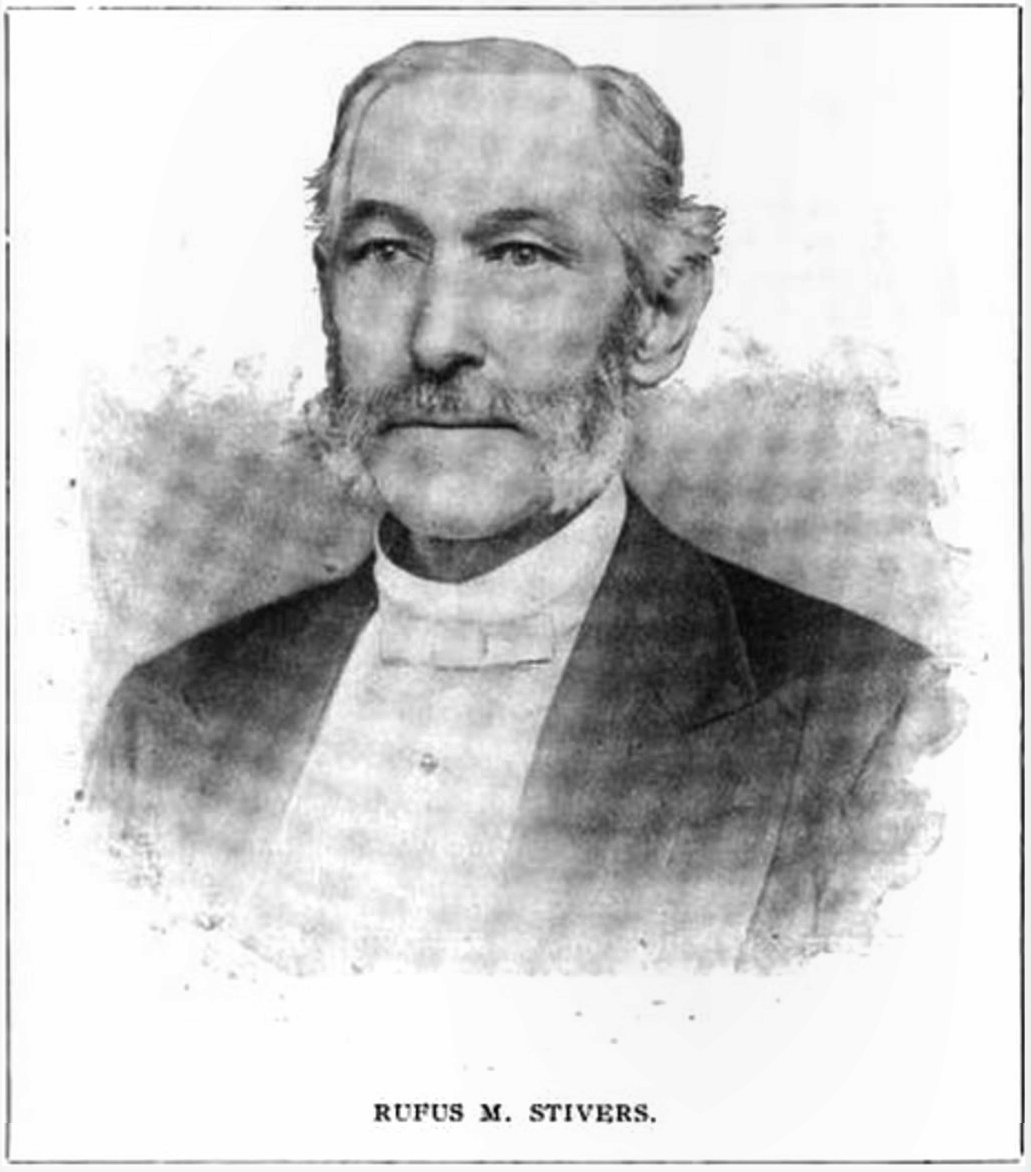

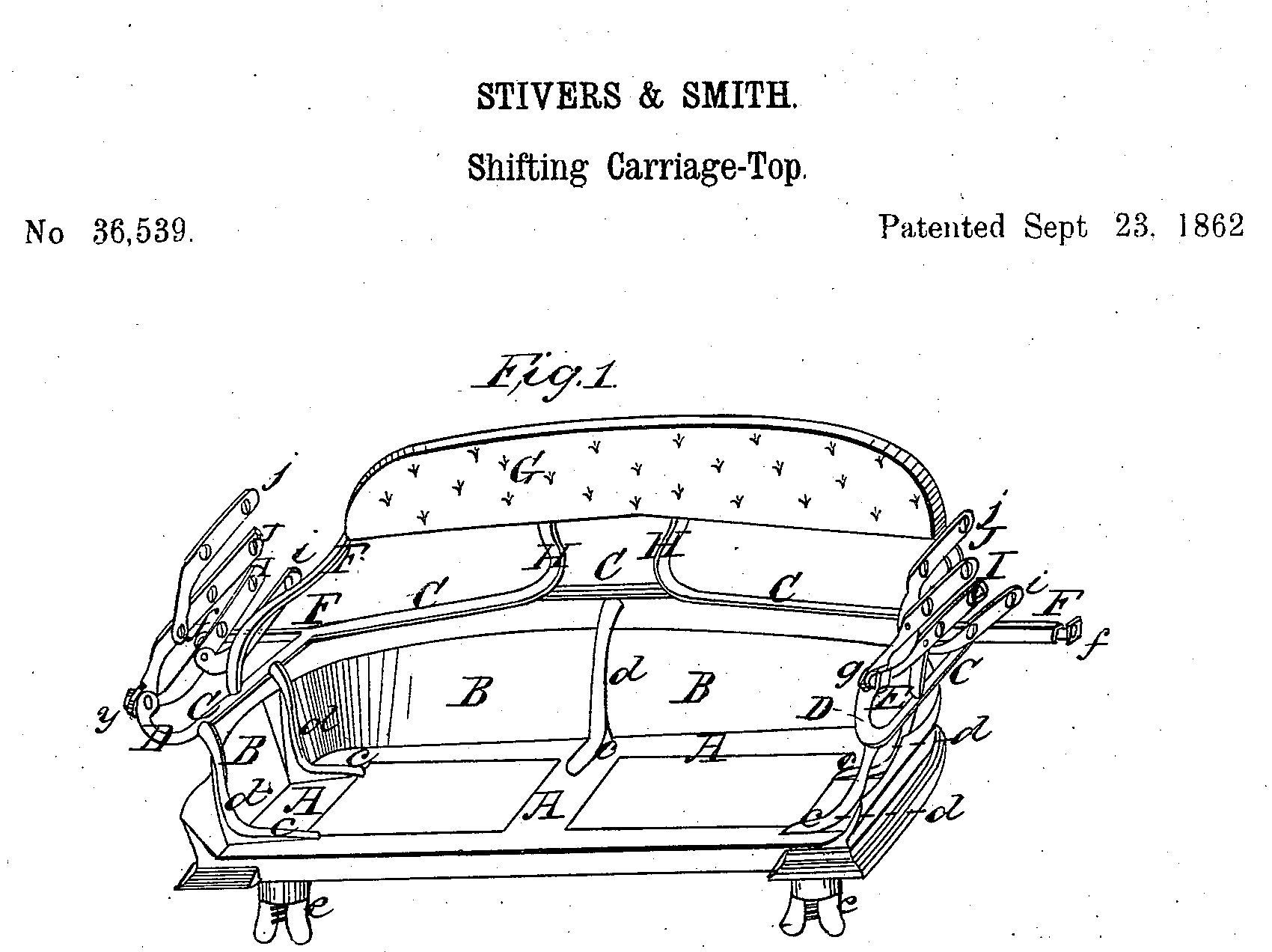

Stivers Patent US36539-0

As mentioned above, 1857 would see a boon in carriage-making shops popping up all over New York. An account given from a history found on the Carriage Museum website reported

as many as 16 companies formed between 1856 and 1858. 5 Stivers & Smith would set themselves apart from the competion by

using Smith's skill and connections in the fabric industry to focus on high quality upholstery and ornate retractable tops. Not only would Smith's capital be a great asset but Smith

was an asset himself. His keen eye, well developed network of suppliers, a working knowledge of value and price, would give Stivers & Smith a clear advantage over their more utilitarian

counterparts. Barely did they get their start when a national financial crisis struck the following year. Weathering that crisis, it was followed a couple of years later by the start of the

Civil War, however, they persevered and provided Smith enough stability, at the age of 35, to step away from Stivers & Smith, retiring and devoting the remainder of his life to the

pursuit of treasure hunting the world's beautiful works of art.

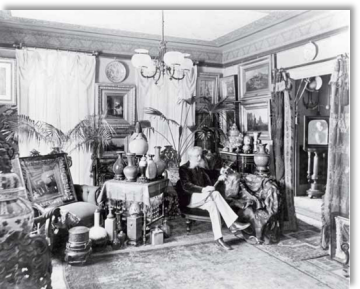

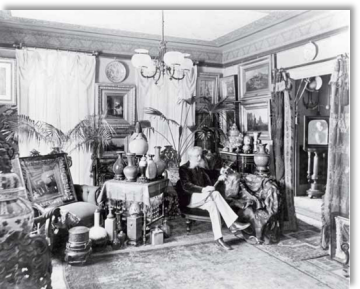

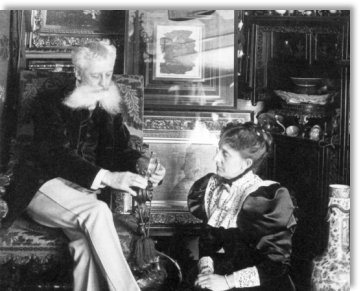

G.W.V. Smith in his study G.W.V. Smith in his study

The legend of G.W.V. Smith is predicated on the presumption that Smith had acquired enough wealth to support himself and his passion for the remainder of his life. Upon closer examination,

this seems unlikely, with just 6 years in the fabric trade and 10 years in the carriage-making industry with its abundant competition and the economic difficulties facing the nation. Smith could be

best described as comfortable rather than a man of "means." What is likely is that his withdrawal from Stivers & Smith was in participation only. His name was still on the business 30 years later

suggesting that his involvement continued most likely as a silent partner. His capital remained in the business and he probably received a stipend or dividend of some sort from Stivers. What is

more intriguing is the possibility that Smith supplemented his collecting with selling and brokering deals for the growing millionaire collector movement. As it is today, collectors often use items

from their collections for trade with other collectors in order to enhance their own collections. It develops into its own economic system with the collectibles becoming commodities themselves.

Smith most likely grew his collection using the collection itself with his talented eye and deal-making skills, buying low and selling high. Smith hardly retired, he simply changed jobs and helped

create a new industry.

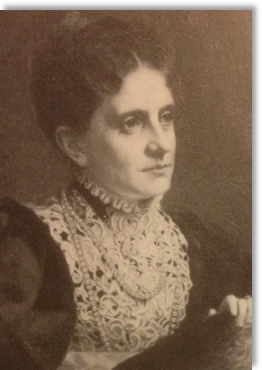

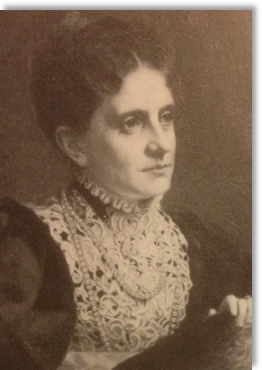

Belle Townsley Smith Belle Townsley Smith

Shortly after leaving his day-to-day duties with Stivers & Smith, Smith would meet his partner-in-crime and future wife Belle Townsley. Introduced by her father, Springfield businessman and

politician, George Townsley, they would marry in June of 1869. Belle and "Walter" as she affectionately called him, hit it off splendidly due to their mutual interest in collecting. Her interest in collecting

was said to rival only that of Walter's. Belle's passion was for collecting fine handmade lace, a skill that was disappearing as the result of the increase and popularity of machine produced lace. His

expertise and connections in the fabric trade most likely opened a whole new world to her.

The two, after a brief stint in New York City, set out to travel and collect abroad in Europe. What

was initially planned to be a two-year adventure turned into 5 years and the Smiths amassed numerous paintings, antiquities and rare treasures. In 1878, the couple, now settled in Springfield, would

put on their first noteworthy exhibition of paintings. It is reported that of the 56 paintings that hung at the show, 36 of them sold. They continued to travel and collect back and forth to Europe from

1882 to 1887, even braving the cholera epidemic during that time which took 230,000 lives throughout the European continent. They are said to have lived in Venice, Italy which was devastated by

the previous epidemic of cholera ending in 1869 before they were married. 6, 7,

8

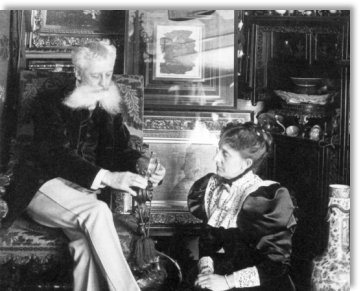

Walter and Belle Townsley Smith Walter and Belle Townsley Smith

Unfortunately, in 1887, the Smiths would be called back home to Springfield for good, due to the illness of her father George. George would pass away in 1888. Shortly after that in 1889, his

wife, whom he married in the same year as Belle and Walter and with whom he had 3 children, would also die. Belle and Walter carried on the care of Belle's 3 step-siblings, the oldest at the time

being just 12 and settled for good in Springfield Massachusetts. Belle's father had a sizable holding of real estate and other business ventures, and Walter would take over the running of his estate.

It is said that the collection the Smiths had been carefully selecting had always intended to be bequeathed to the city of Springfield. We cannot ascertain if this is a matter of fact or legend. However,

we do know that Smith held a very strong conviction, and perhaps the driving force behind his pursuit of collecting that art, was that it was meant to be shared with the world. He strongly

believed in its educational and inspirational value. In 1887, the Smiths loaned their collection to the Springfield Library Association.

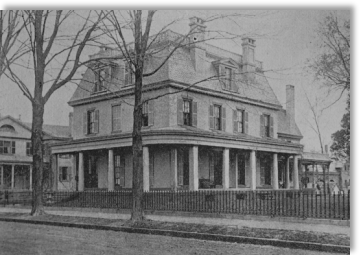

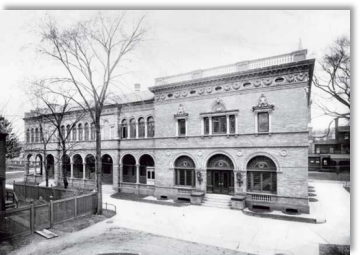

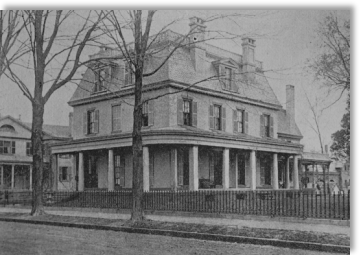

George Bancroft House George Bancroft House

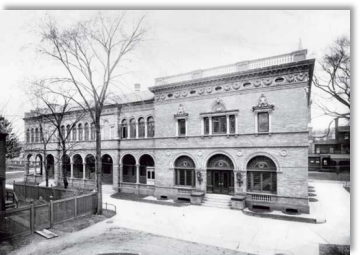

Two years later, in 1889, Smith proposed to give the entire collection to the city, provided they would build a fireproof structure to house it. The city agreed, and built the Italian-style Palazzo building.9

In April 1896, the "Art Museum" housing the Smith collection, including Belle's Italian cutwork lace and Walter's remarkable collection of Chinese Cloisonné opens. In 1902, the Smiths would buy the

George Bancroft house on Chestnut Street just behind the museum located on State Street. Belle and Walter could simply walk across their yard to the museum.

In 1912, the couple held

a special exhibition of Belle's Italian cutwork lace, Rose-point lace, Spanish Lace, and varieties of French Lace. Belle's laces were described as "rare treasures" and "masterpieces of fine work" by the

local newspapers. The exhibit attracted many Springfield women, who were interested in the "Lace Revival" of collecting antique and

handmade lace.10

G.W.V. Smith Museum, 1896 G.W.V. Smith Museum, 1896

On February 7, 1914, the formal deed of gift by which the collection became forever the possession of Springfield Library Association was executed. The legal title by which the collection is known, is

the George Walter Vincent Smith Collection. The collection of treasures included as the deed recites, "a very valuable choice and extensive collection of ceramics, bronzes, paintings, arms, textiles, lacquers,

cloisonné, enamels, silverware, furniture, laces, books, manuscripts, jades, and many other art objects and curios."11 Smith also announced his purpose

was to provide by endowment, the means for the proper perpetual care of the collection. It is a shame, that Belle's name is not included in the name of the collection. Her contribution was every bit as valuable

as her husband's. If not for her, the collection might well have ended up in New York City, Bridgeport, Connecticut or Amenia, New York.

J.H. Miller Galleries, Inc. J.H. Miller Galleries, Inc.

Smith would continue the duties of maintaining the collection, adding to it and improving it as the collection's director after the formal transfer of gift. As such, here is

where artist Robert Strong Woodward finally enters the picture. In 1921, Smith had purchased two of Woodward's paintings, Early Moonlight and In Apple Blossom Time to hang in

the collection. Then in 1922, Smith would buy two more Woodwards from the Twelfth Annual Free Exhibition Oil Paintings By Local and Well-known American and Foreign Artist Exhibition held at the J.H.

Miller Galleries Inc. Springfield (MA). However, not without some controversy over the price of Woodward's 40 x 50 painting, Under the Winter Moon.

Woodward had already let J.H.

Miller talk him into lowering his asking price from $1,000 to $750 for the exhibition. This is despite Under the Winter Moon having been previously exhibited and highly praised twice before, one being

the National Academy's annual exhibition. Also, Smith, having already bought Through the Hills in May for half Woodward's asking price of $450, now offered just $450 for the much larger and

exceptionally well-painted Under the Winter Moon. Woodward, in turn, wrote two letters, one to Smith personally and the other to J.H. Miller who forwarded it to Smith. The letters were found in

the Springfield Museum Archives. We do not know what Smith's response was to Woodward or for what price they finally settled. Smith decreed in his will, that all his correspondence and papers

be destroyed upon his death. However, both Under the Winter Moon and Through the Hills in May remain in the collection to this day.

The legacy the Smiths left behind

is immeasurable. They were both the product of their times, as we all are. A period of expansive industrial growth, machination & development and huge fortunes to be had or gotten. Unprecedented wealth

and societal change. There was a strong national movement towards preservation and keeping a connection to simpler times, as well as, the preservation of a past where the skill of hand is what made

something rather than the precision of a machine. All of this influenced a movement nationally to preserve pre-industrial craftsmanship and its beauty. A boom in museums featuring these items, often

donated by the guilded millionaires and industrialists of the age to give back to the people and leave a legacy in their name. The summation of Smith's legacy was best described in an undated article by the

Springfield Republican:

"The spiritual appeal will be there forever a writer of books can put his single soul with its message between

covers. Mr. Smith has gathered for us his faithful work of thousands of souls as expressed in superior craftsmanship. Through him they are to teach us. As a master in appreciating them he has assembled a

noble company for our service. This is what Mr. Smith has done with his life and his money, -- and he has done well. Few men have built upon the foundation so enduring, so worthy of respect, of tribute and of

gratitude." 12And the Smith's collection endures to this day. As recently as 2012, the General Counsel of Japan for Boston, Takeshi Hikihara, visited the museum specifically to view its collection of more than 500

examples of Japanese arms and armor, including the six full suits of armor. Mr. Hikihara is the official representative for the Japanese government in New England, said of the collection, "It's really incredible,

isn't it? What I love about the collection is that it shows Japanese arts and culture over several different time periods, right up to the 18th century... Cultural exchanges like this are an important part of our

work." 13 Exactly what Walter and Belle would have loved to hear. It truly can be said their gift is the one that keeps on giving.

Footnote Format: Return (↩) to footnote, footnote number, source and any related links of available.

|

|