New England Drama

New England Drama by Buckland artist Robert Strong Woodward (1885-1957)

An oil painting of the Goddard Farm on Hog Hollow Road in Buckland in 1930.

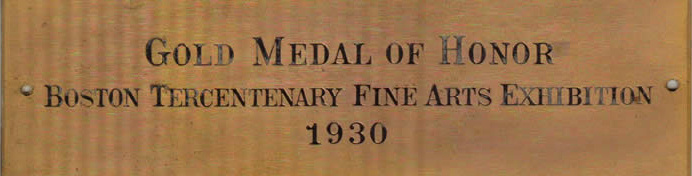

Winner of the 1930 Boston Tercentenary Exhibition

Gold Medal of Honor for best oil painting

About the Painting:

New England Drama by Buckland artist Robert Strong Woodward, depicts a local landscape in winter. In his own words from his painting diary, it looks from the "mowing edge above the house of Goddard's farm looking toward Buckland village and the mountains of Town Farm Hill." The Goddard farm on Hog Hollow Road is now the Toy place, and Town Farm Hill is better known as Charlemont Road; the long-vanished town farm was located at the top of the hill across from Avery Road.

Close-up of New England Drama showing the man, the horse, and the dog

New England Drama has all the hallmarks of Woodward's finest work: strong composition, assured draftsmanship, and an elusive poetic quality often admired by his reviewers. Harry Elmore Hurd, in his article in the Boston Breeze of June 5, 1931, called it "a Snow-Bound in oil: it is as characteristically New England as [John Greenleaf] Whittier's classic poem."

Woodward sent New England Drama to the Boston Tercentenary Exhibition, held at the Horticultural Hall, in 1930, where it received the Gold Medal of Honor as the best oil painting in the exhibition. He kept the medal among his effects at his desk in the Southwick studio on Upper Street.

The Myles Standish Hotel (Myles Standish Hall)

Today the old hotel is a dormitory for Boston University

Woodward wrote in his painting diary in 1941, "they think so much of it they have kept it for a number of years." Though they "begged to let it remain", he assured potential buyers that he could obtain it anytime he wished. The hotel eventually closed in 1949 and the building was sold to Boston University and converted into a dormitory. New England Drama returned to the Southwick place. Badly deteriorated, it underwent complete restoration in 2004 at the Williamstown Regional Art Conservation Laboratory, Inc. in Williamstown, Massachusetts.

Through the generosity of Dr. Mark and Barbara Purinton, New England Drama has found a fitting home in the Buckland Town Office. Now its admirers have the rare privilege of seeing a masterpiece of Robert Strong Woodward, who lived and worked in Buckland, but whose genius extends far beyond its hills.

Art criticism of New England Drama :

Most art critics had high praise for New England Drama.

"New England Drama (is) one of the outstanding landscapes - a snow scene with farm buildings, rather in the grand manner."

Springfield Republican, review of the Art League's 14th Annual Show at City Library, on March 12, 1933

Springfield Republican, review of the Art League's 14th Annual Show at City Library, on March 12, 1933

A "remarkable winter panorama of snow covered hills, Gold Medal winner at the 1930 tercentenary exhibitions."

Northampton Hampshire Gazette's article on an art exhibit at Williston Academy, May 19, 1933

Northampton Hampshire Gazette's article on an art exhibit at Williston Academy, May 19, 1933

"Robert Strong Woodward, whose oils are on view here, is not interested in psychological problems and imaginative subjects, but in reproducing realistically such colorful manifestations of nature as Autumn foliage or a bed of geraniums growing under a New England window. It is entirely objective and conservative painting, colorful and straightforward. Mr. Woodward's most striking painting is a New England panoramic snowscape. For the most part the pictures portray New England scenes. Opened December 13; continues through this month".

Edward Alden Jewell, the New York Times critic, review of the Woodward's exhibition at the Macbeth Gallery in New York City on December 18, 1932

Edward Alden Jewell, the New York Times critic, review of the Woodward's exhibition at the Macbeth Gallery in New York City on December 18, 1932

"From the viewpoint of color alone this group of pictures is a complete lesson of the variety and richness of our native landscape, just as they are a whole summary of what is truly American art.

Mr. Woodward lets us see in his vast expanse of low country and hills the true sense, the grave feeling, of what he calls "New England Drama " in its snowbound bitterness."

The New York American in an article titled "Fine Exhibitions Now to be Seen in N.Y. Galleries" on December 31, 1932

Mr. Woodward lets us see in his vast expanse of low country and hills the true sense, the grave feeling, of what he calls "New England Drama " in its snowbound bitterness."

The New York American in an article titled "Fine Exhibitions Now to be Seen in N.Y. Galleries" on December 31, 1932

"Paintings of New England, by Robert Strong Woodward, reveal an intimacy with the country which these landscapes portray that draws the visitor who knows and loves New England irresistibly to them ... here is an equally real America, untouched and unspoiled, still the "unravished bride of loveliness," the rugged yet beautiful world of these New England hills and deep valleys ... Mr. Woodward has seized the mood of this austere yet enchanting country and has rendered its native character without idealization in sympathetic and understanding terms ... [with] poetic statements of the real quality of New England countryside and living. The artist, however, places esthetic reliance qualities on solid qualities of design which carry his conceptions convincingly. His structure and composition have no formula, but serve him in good stead in each theme ... [showing] the power and beauty of these landscape canvases."

Margaret Breuning, NY Post column of December 22, 1932, Review of the exhibition at the Macbeth Galleries in New York City

Margaret Breuning, NY Post column of December 22, 1932, Review of the exhibition at the Macbeth Galleries in New York City

"The best thing about the work that Robert Strong Woodward is showing at the Macbeth gallery is the fresh point of view that it reveals ... The composition is as sound as it is personal, unforced and all through the picture I rest contentedly on the artist's draftsmanship, one of his leading resources ... There is enough solidly constructed work in this exhibition to carry Mr. Woodward far. He has the root of the matter in him."

Royal Cortissoz in the NY Herald Tribune on December 18, 1932

Royal Cortissoz in the NY Herald Tribune on December 18, 1932

But these latter two critics also found Woodward's surfaces too "painty" - whatever that means.

"Color is not so happy, except in a few instances, while a certain paintiness of surfaces is also to be regretted."

Margaret Breuning in the NY Post

Margaret Breuning in the NY Post

"Mr. Woodward leaves much of his work in one respect needful of further development. His color, though sometimes powerful,..has not quality enough, and his surfaces are often too "painty." The latter difficulty is encountered particularly in the big New England Drama, in which the white clad mountains cry aloud to be tempered in tone, made richer and mellower."

Royal Cortissoz in the NY Herald Tribune

Royal Cortissoz in the NY Herald Tribune

A Woodward supporter, "J.F." from Deerfield sent in this rebuttal letter to the editor of the NY Herald Tribune (unprompted by Mr. Woodward):

"To the New York Herald Tribune:

My attention was called this morning to the issue of your paper containing Mr. Cortissoz's appreciation of Robert Strong Woodward's work now on exhibition at the Macbeth Galleries. The appraisal of values was noteworthy and for the most part valid. But the comments on that remarkable canvas New England Drama were astonishingly irrelevant. To suggest mellowing and softening the high points of stark tragedy is virtually to propose leaving Hamlet out of the play.

The strength of Woodward's work lies in its rhythmic vitality, a quality he has obviously secured by the effective use of his medium - paint. If the current slang for that most desirable achievement is "painty," then by all means let us beg the gods to send us more artists of the "painty" pattern."

J.F., Deerfield, Massachusetts, Letter to the Editor, New York Herald Tribune, December 30, 1932

My attention was called this morning to the issue of your paper containing Mr. Cortissoz's appreciation of Robert Strong Woodward's work now on exhibition at the Macbeth Galleries. The appraisal of values was noteworthy and for the most part valid. But the comments on that remarkable canvas New England Drama were astonishingly irrelevant. To suggest mellowing and softening the high points of stark tragedy is virtually to propose leaving Hamlet out of the play.

The strength of Woodward's work lies in its rhythmic vitality, a quality he has obviously secured by the effective use of his medium - paint. If the current slang for that most desirable achievement is "painty," then by all means let us beg the gods to send us more artists of the "painty" pattern."

J.F., Deerfield, Massachusetts, Letter to the Editor, New York Herald Tribune, December 30, 1932

Woodward himself expressed his dismay to Mr. Macbeth of the Macbeth Galleries in a letter dated December 20, 1932:

" ... I was bitterly surprised and depressed over Cortissoz's review in the Times [he meant the Herald Tribune]. He had taken the initiative himself of asking if I wouldn't have a New York show this winter - stating it would leave "a deep impression." He spoke of the work as having "personal force" and "fine vitality" - says it is work that "will last." All this I know myself - and all the world will know it in time, if I can in some miraculous way keep body and soul together to keep painting - but why the devil did he have to give the negative impression as he did in Sunday's reviews? Why state that surfaces are too "painty?" Mine are in conservative control beside of those of Jonas Lie, or John Folinsbee - or Robert Henri, or Redfield himself - all acclaimed as arrived masters? In speaking of "Autumn Blaze," in one sentence he calls it "an uncommonly fine burst of color" - and the very next says its "color ... has not quality enough!" How do you solve that? And as to the large New England Drama - it is the one 40 x 50 among the several I wanted to show which I included, because I was sure it would especially appeal to Cortissoz!

So for him to say that the "mountains ... in it ... cry aloud to be tempered in tone - made richer and mellower" - I am utterly amazed - for there is no point of truth to the negative statement. Winter mountains are cold, hard metallic things when as close to the foreground as in New England Drama - and mine in that picture were controlled and mellowed almost to a weakness - for the point of the design. They represent one of my most subtle attempts in varying whites! How strange! Cortissoz must have had bad indigestion the day he reviewed the shows! And Jewell in claiming that it was all objective painting and not subjective - also fell far from the mark. My landscapes are not fogged, and atmosphered and given a personal twist of tone - not because I couldn't do it - but because I consider the greatest art does not admit of such personal twists and biases; - but they are so exactly true in impression and color relation and subjective expression, that they fool even the experienced critics, who consider them, superficially, as merely exact copies of nature and so, entirely objective. I'll show them all yet - if I can but live long enough to do so!"

Robert Strong Woodward, letter to Mr. Macbeth of the Macbeth Galleries, December 20, 1932.

So for him to say that the "mountains ... in it ... cry aloud to be tempered in tone - made richer and mellower" - I am utterly amazed - for there is no point of truth to the negative statement. Winter mountains are cold, hard metallic things when as close to the foreground as in New England Drama - and mine in that picture were controlled and mellowed almost to a weakness - for the point of the design. They represent one of my most subtle attempts in varying whites! How strange! Cortissoz must have had bad indigestion the day he reviewed the shows! And Jewell in claiming that it was all objective painting and not subjective - also fell far from the mark. My landscapes are not fogged, and atmosphered and given a personal twist of tone - not because I couldn't do it - but because I consider the greatest art does not admit of such personal twists and biases; - but they are so exactly true in impression and color relation and subjective expression, that they fool even the experienced critics, who consider them, superficially, as merely exact copies of nature and so, entirely objective. I'll show them all yet - if I can but live long enough to do so!"

Robert Strong Woodward, letter to Mr. Macbeth of the Macbeth Galleries, December 20, 1932.

Finally, the "painty" critic himself, Royal Cortissoz, wrote in a personal letter to Woodward on January 2, 1933, a further clarification - and an assurance that he did not believe Woodward had put "JF" up to his letter:

"Dear Woodward:

A happy new year to you! I begin the new year with a letter to you which I am very glad to write. I cannot too soon disabuse your mind of any idea that a thousand "counter criticisms", from any source, could consciously or unconsciously affect my attitude toward your work. That is determined solely by the work itself. I was merely amused by the letter to which Mr. Macbeth referred in his letter to you. Obviously it came from some admirer of yours but whoever it was was very foolish. I had been talking about "quality" in paint, a term which you and I perfectly well understand. The letter writer retorted by dragging in rhythm, a totally different thing. Naturally I smiled but I was glad to have the item printed, if only to show that you have your staunch partisans.

I, as you know, am also one of them. I have a well founded belief in your work. Since you know this and since you write so frankly I will tell you in my turn a little more of what I was driving at. There is a delicate moment in which the insensate paint, under the artist's hands, takes on a patina that makes it a little more than paint, makes it a sensuously beautiful surface. Time, as you know, often accomplishes this subtle mutation but it is within the artist's power to achieve it. I believe it is within your power and I urge you to meditate upon it. As a matter of fact I greatly admired the construction of the big mountain picture. Just because of its importance I paused there upon the qualities I had raised. I was sorry to find the mountain there "painty", as I said, when I felt that by longer manipulation of your tones you might have got the "quality" of which I venture to speak so much. It is a terribly important element, this of giving a richer density, a more personal accent, to mere painted surface. But enough of my moralizing. I only indulge in it because I feel that we are friends and that you will take in good part my endeavor to suggest what I think would heighten the value of your already valuable work.

And grasp, too, really grasp, the fact that I had not thought of you as inspiring the letter in question and couldn't possibly be influenced by it in any way.

... I do hope the new year mends for you and brings more of brightness into your life. Meanwhile you have your beautiful work. May you wax stronger and stronger in that, going on from one success to another. Be sure that I shall "watch out" for what you do."

Royal Cortissoz, personal letter to Woodward, January 2, 1933

A happy new year to you! I begin the new year with a letter to you which I am very glad to write. I cannot too soon disabuse your mind of any idea that a thousand "counter criticisms", from any source, could consciously or unconsciously affect my attitude toward your work. That is determined solely by the work itself. I was merely amused by the letter to which Mr. Macbeth referred in his letter to you. Obviously it came from some admirer of yours but whoever it was was very foolish. I had been talking about "quality" in paint, a term which you and I perfectly well understand. The letter writer retorted by dragging in rhythm, a totally different thing. Naturally I smiled but I was glad to have the item printed, if only to show that you have your staunch partisans.

I, as you know, am also one of them. I have a well founded belief in your work. Since you know this and since you write so frankly I will tell you in my turn a little more of what I was driving at. There is a delicate moment in which the insensate paint, under the artist's hands, takes on a patina that makes it a little more than paint, makes it a sensuously beautiful surface. Time, as you know, often accomplishes this subtle mutation but it is within the artist's power to achieve it. I believe it is within your power and I urge you to meditate upon it. As a matter of fact I greatly admired the construction of the big mountain picture. Just because of its importance I paused there upon the qualities I had raised. I was sorry to find the mountain there "painty", as I said, when I felt that by longer manipulation of your tones you might have got the "quality" of which I venture to speak so much. It is a terribly important element, this of giving a richer density, a more personal accent, to mere painted surface. But enough of my moralizing. I only indulge in it because I feel that we are friends and that you will take in good part my endeavor to suggest what I think would heighten the value of your already valuable work.

And grasp, too, really grasp, the fact that I had not thought of you as inspiring the letter in question and couldn't possibly be influenced by it in any way.

... I do hope the new year mends for you and brings more of brightness into your life. Meanwhile you have your beautiful work. May you wax stronger and stronger in that, going on from one success to another. Be sure that I shall "watch out" for what you do."

Royal Cortissoz, personal letter to Woodward, January 2, 1933

In 1935 Howard Devree of the New York Times, reviewing another Woodward show at the Macbeth Galleries, neatly summarized the essence of his painting:

"Woodward has a feeling for the panoramic values in landscape. He has, too, succeeded in imbuing his material with a sense of familiarity - leaving the beholder with the feeling that this is country one has visited but failed to appreciate. Here are the weather-beaten dwellings epitomizing a passing New England."

Howard Devree, New York Times, 1935

Howard Devree, New York Times, 1935

Janet Gerry

February 2007